Cooperatives have been part of the fabric of the Montana economy nearly as long as we have been a state. Their footprint is significant in industries that are central to the state’s economy, including agriculture and food processing, banking and credit, electric power distribution and manufacturing. While their presence is most notable in Montana’s rural communities, they are an important economic driver in urban areas as well.

The long-standing presence of these customer-owned organizations in cities and communities across the state has at times made their operations less visible to the general public. Yet they are jointly responsible for thousands of jobs, millions of dollars of income and investment, and the stability and viability of countless members and customers who do business with them. Assessing and presenting the economic contributions made by these organizations to the Montana economy is a useful way of highlighting their importance.

The Bureau of Business and Economic Research (BBER) has conducted an analysis that addresses the research question, “What would the economy of the state look like if cooperatives did not exist?” The question is clearly hypothetical – no conceivable policy could (or should) make this event actually occur. Rather it is a way of highlighting how the operations of Montana’s cooperatives connect with the rest of the economy.

Montana cooperatives are arguably among the most connected forms of business in Montana. Their collective ownership, the nature of the products and services they provide, and the wide geographic scope of their activities across the state puts them in close contact with customers and workers everywhere. And so, their presence in the economy can be expected to be felt widely as well.

Cooperatives in Montana

The cooperative model for organizing businesses dates to the industrial revolution in Europe in the 18th century. Its roots in this country are almost as old – the first cooperative business here was a mutual fire insurance company, founded in 1752 by Benjamin Franklin and still in operation today. Since the 1930s, cooperatives have grown, consolidated and evolved into key players across a wide spectrum of business activity, including agriculture, energy, credit, telecommunications and a variety of consumer businesses. Some agricultural cooperatives today rank among the country’s largest businesses of any kind, and operate in dozens of states.

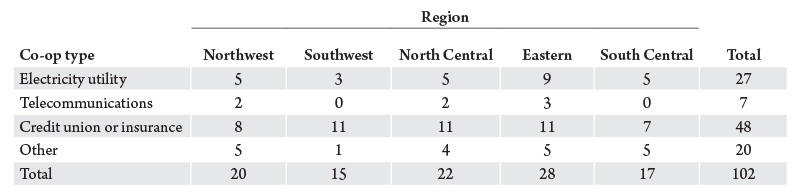

In Montana, cooperatives have had a strong presence. The 101 cooperatives included in the analysis reported in this article included 27 electric co-ops, 48 credit unions and insurers, seven telecommunications cooperatives and a number of elevators, distributors, and other agricultural and nonagricultural businesses.

As shown in Table 1, more than a quarter of all of the cooperatives included in this study are located in eastern Montana, a region that contains only 7% of the state population. Included in the table’s “other” category are grain elevators, energy distributors, a restaurant and an oil refinery.

When one (hypothetically) removes the sales, production, employment and income of cooperatives from the economy, the reduction in economic activity is much larger than the cooperatives themselves, since the spending of the organizations and their workers is received as income for other businesses and governments within their communities and in the state. Thus, the activity of cooperatives supports many jobs and livelihoods beyond those with a direct connection to the organizations themselves.

Ownership of Montana cooperatives is similarly varied. Two-thirds of the cooperatives included in this analysis are owned by individuals, typically customers. Of the remainder, 13% are worker-owned, 10% are owned by area farmers and ranchers, and 10% are owned by other cooperatives.

The Economic Contributions of Montana Cooperatives

Our approach to this research involved constructing two scenarios for the economy. The first is a baseline, status quo projection where no changes are made. The second is a “no cooperatives” scenario where the spending, production, sales and employment of cooperatives is subtracted from the economy. In the second case, the economy comes to a new equilibrium, or resting point, as other jobs and activities in the rest of the economy adjust to the absence of the cooperatives. The difference between the economic activity actually observed and this “no cooperative” scenario is the total economic contribution of Montana’s cooperatives.

Since this “no cooperative” Montana economy cannot be directly observed, it must be constructed by means of an economic model. BBER uses its policy analysis model, leased from Regional Economic Models, Inc. (REMI) and constructed explicitly for this purpose, to conduct this analysis. The REMI model is a well-known, well-respected tool for economic analysis that has been used in hundreds of studies and is the subject of dozens of peer-reviewed scholarly articles.

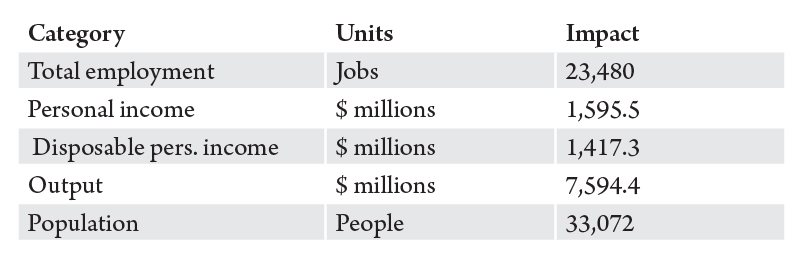

Specifically, we find that an economy with the cooperative businesses included in this study, representing more than 5,000 jobs, ultimately produces an economy that has:

- 23,480 additional permanent, year-round jobs, which are ultimately supported by the spending and production of the co-ops;

- Almost $1.6 billion each year in additional income received by Montana households, of which more than $1.4 billion is after-tax income, available for spending elsewhere in the economy;

- An increase in the gross receipts of business and nonbusiness organizations across the economy of $7.6 billion per year; and

- More than 33,000 additional people, as workers and their families, are attracted to and remain in Montana due to expanded economic opportunities.

These impacts represent permanent, ongoing contributions to the state economy, and are significantly larger than the employment and spending of the cooperatives themselves. They represent the comparison between the actual economy, which includes cooperatives, with an artificially constructed, “no cooperatives” scenario of the economy, which removes co-op employment and spending.

The figures shown in Table 2 are the impacts of all cooperatives as a group, which include credit unions, electric cooperatives, telecommunications cooperatives, farm-related co-ops and others. All of these categories of cooperatives represent different kinds of economic activities, with different products and services, different technologies, and different economic footprints. Yet they share in common impacts which ultimately make the economy larger.

Those impacts by type of cooperative, summarized in Table 3, are clearly substantial. The first three categories – credit unions, electric cooperatives and telecommunications cooperatives, consist of cooperatives of different sizes and locations who are in the same line of business. The different size of their overall impacts reflects the number of individual cooperatives contained in each (from 47 credit unions to six telecommunications co-ops), as well as differences in the nature of their businesses.

The remaining two categories contain more diverse collections of businesses. The CHS petroleum refinery, located in Laurel, Montana, is sufficiently different from the rest to merit its own category. Its highly capitalized, high value-added production processes and its highly compensated workforce underpin its outsized impacts. The remaining category includes a wider spectrum of businesses relating to agriculture, including grain elevators, distribution and wholesaling activities.

Conclusion

Montana’s customer-owned cooperatives are a diverse group of businesses that share one aspect in common, namely their close connections to the communities in which they operate. Those connections make what those businesses do and where they do it of special importance, and combine to create a substantial economic impact.

Our finding is that the operations of cooperatives makes the economy significantly larger, more prosperous and more populous. The more than 23,000 jobs, the $1.6 billion in annual personal income, the $7.4 billion in economic output every year, and the 33,000 additional people in Montana that exist because of their operations is vivid testimony to the substantial economic benefits their presence brings.