The American energy boom began with improvements in technology. Advances in geophysics, nanotechnology, engineering and production management led to the shale-energy revolution and a dramatic increase in U.S. energy production. Increases in the supply of natural gas and crude oil have come from locations as varied as the Mid-Atlantic states, the Montana-North Dakota border and traditional supply areas, like Texas and Oklahoma.

This increase in supply has recently led to a dramatic drop in oil prices – there have been a number of media stories about its impact on the oil industry as a whole and the possibility that an oil bust could return new production areas to their pre-boom economic conditions. This article attempts to put events into perspective by looking at the Bakken area on the Montana-North Dakota border over the entire boom and bust cycle.

Two areas will be analyzed: Richland County, Montana (Sidney), and Williams County, North Dakota (Williston). The oil wells themselves are distributed over the entire Montana-North Dakota border area, but these two communities are the largest in the region and serve as trade and service centers. Employment and income data is analyzed to identify local economic trends, but impacts on infrastructure, housing, crime and other social factors will not be examined here.

The Beginning

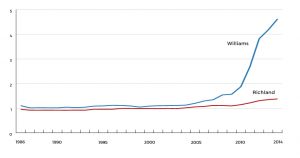

Richland and Williams counties weren’t always booming. As Figure 1 shows, both economies experienced stagnation during the past 30 years. From 1986 until the mid-2000s, total nonfarm jobs in each county did not grow. There were small upward blips between 2007 and 2009, but the Bakken boom really began in 2011. Since then growth has been larger in North Dakota than Montana.

Nonfarm employment in Williams County increased about 140 percent from 2010 to 2014, while Richland County grew about 33 percent. The difference between the two areas was caused by the characteristics of the oil deposits, the expertise of the drillers and other factors. Most experts agree that differences in the tax rates between the states was not a major factor.

The Boom

From 2011 to 2014, there were boomtown atmospheres in Sidney, Montana, and Williston, North Dakota. Oil drilling rigs multiplied, traffic became astonishing and there were no vacancies in the few existing motels. The streets were packed with petroleum engineers, drilling managers and environmental specialists, along with roustabouts and roughnecks who put in long days.

Not only were the streets packed with new people, but new jobs that paid well. Table 1 provides employment and average annual wages and salaries for oil related industries in Richland and Williams counties. Most of the industry titles are self-explanatory – trucking was included as an oil-related industry because of the large number of vehicles needed to haul mining materials into the field and oil from the wells to catchment areas.

Table 1. Employment and Average Annual Wages and Salaries for Oil Related Industries, Richland and Williams Counties, 2014. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, QCEW.

| Richland County, MT | Williams County, ND |

| NAICS Code and Title | Employment | Average Annual Wages | Employment | Average Annual Wages |

| 211 Oil and Gas Extraction | 317 | $117,500 | 1,035 | $119,300 |

| 213111 Oil and Gas Drilling | 25 | $109,800 | 3,820 | $107,700 |

| 213112 Oil and Gas Support Services | 642 | $88,500 | 9,815 | $105,600 |

| 4842 Specialized Trucking | 403 | $70,700 | 3,197 | $81,800 |

High wages were paid mostly to well-educated and skilled professionals who did not live in the area prior to the boom. But what about the locals? As it turns out, their job opportunities and wages were also favorably impacted by the boom.

Table 2 presents information about the accommodations industry, which has traditionally paid low wages and is often mentioned as providing entry-level positions for those with few skills. Employment in the Montana accommodations industry increased 9 percent from 2010 to 2014, while corresponding growth in North Dakota rose 41 percent. In Richland County, it grew 80 percent, but in Williams County it increased 216 percent. Average wages in Montana rose 14 percent during this four year period, while wages North Dakota rose 50 percent. Once again, the increases in Richland and Williams counties were well above their respective statewide figures – 108 percent in the former and 124 percent in the latter.

Table 2. Percent Changes in Employment and Average Wages, Accommodations Industry (NAICS 721), 2010-14. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, QCEW.

| Area | Change in Employment | Change in Wages per Worker |

| Montana | 9% | 14% |

| Richland County | 80% | 108% |

| North Dakota | 41% | 50% |

| Williams County | 216% | 124% |

Similar conclusions were found for construction, professional services and other industries. Overall, employment opportunities and wage growth improved in most sectors of the economy within oil boom regions. But the economic impact of the oil boom was not confined to eastern Montana and western North Dakota. A number of Montana businesses across the state service the oil industry and due to the local housing shortage, many workers from urban areas commuted to jobs on the Montana and North Dakota sides of the border.

The American Petroleum Association compiled a list of 224 firms in Montana that are vendors to the petroleum industry – their locations across the state are reported in Table 3. Communities are identified because the locations were reported by ZIP code rather than county boundaries. Allowing for a few approximations, petroleum industry vendors – ranging from catering to oil field vehicle servicing – were in 36 of Montana’s 56 counties. The statewide distribution of vendors can be seen as far away as Missoula and the Flathead, each containing a number of firms.

Table 3. Vendors to Montana’s Oil Industry, By Community. Source: American Petroleum Institute.

| Community | Vendors |

| Billings Area | 49 |

| Sidney Area | 22 |

| Missoula Area | 12 |

| Great Falls Area | 10 |

| Bozeman Area | 7 |

| Helena Area | 6 |

| Flathead Area | 5 |

| Butte-Anaconda Area | 4 |

| Miles City Area | 3 |

| All Other Areas | 106 |

| TOTAL | 224 |

Bakken economic impacts have also dispersed across Montana by the commuting of workers. Because housing was scarce near the exploration and drilling sites, many workers lived in temporary quarters and returned to their homes between work sessions. These commuters were persons working in the Bakken, but living and spending much of their incomes elsewhere.

A U.S. Census Bureau report identified commuters’ places of work and residence in 2014. As shown in Table 4, a sizable numbers of workers travel from Montana’s major urban areas to jobs in the Bakken. For example, about 229 people commuted from the Billings area (Yellowstone County) to jobs in Richland County, while another 298 worked in Williams County, North Dakota.

Table 4. Workers by Place of Work and Residence, 2014. Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

| Place of Work |

| Residence | Richland County, Montana | Williams County, North Dakota |

| Flathead County | 29 | 241 |

| Missoula-Ravalli Counties | 39 | 384 |

| Cascade County | 53 | 266 |

| Lewis and Clark County | 18 | 169 |

| Gallatin County | 34 | 248 |

| Yellowstone County | 229 | 298 |

| Butte-Anaconda | 5 | 132 |

| Custer County | 137 | 195 |

| Dawson County | 424 | 226 |

A Bust or a Pause?

It is not hard to identify when things began to turn south. As shown in Figure 2, trends were favorable until late spring 2014. Oil prices remained high and total employment was growing in both Richland and Williams counties. Then in June 2014, oil prices started to drop and plummeted to half by early 2015. There was a deathly silence in oil producing areas as people waited for the shoe to drop. Richland and Williams counties continued to see modest growth as late as 2014 in nonfarm employment, then in early 2015, about six months after oil prices started to drop, nonfarm employment in both Richland and Williams counties turned downward and continued to decline into early 2016 (the latest data available for employment).

The big news is not that these local economies started to decline, but that they have not declined more. Which begs the question – why haven’t the declines been more like earlier energy busts, such as the mid-1980s? The decreases in nonfarm employment from January 2015, when the declines began in earnest, to March 2016 was about 16 percent in Richland County and roughly 38 percent in Williams County. Both are still well above their pre-boom levels of January 2011.

Plummeting oil prices have led to an almost complete cessation of drilling activity in the Bakken and other oil producing areas of the country. Even so, oil continues to be extracted from existing wells, meaning continued employment for workers in these sectors. In terms of the four sub-categories of the oil industry shown in Table 1, employment in the extraction sector has risen, while the drilling category has almost disappeared. Declines in the other NAICS industries, such as support and trucking, remain relatively modest.

But the current situation cannot continue indefinitely. There cannot be a continued extraction of oil without a resumption of drilling. Even though shale wells have a very long tail – where production continues, but at a very small volume – sooner or later the existing wells will run dry.

The Future

The very existence of the Bakken is closely tied to improved technology. Geologists and petroleum engineers have long known of the potential of shale oil deposits. The problem was always getting to the oil, as there were no methods to efficiently gather the oil from these deep pools. But advances in fracking, horizontal drilling and other technologies provided the means to extract it.

Significant and rapid decreases in costs are often associated with the introduction of new technologies – practitioners learn what they are doing and how to do it better. In addition, within the shale industry, there was the belt tightening and squeezing out of inefficiencies associated with the recent drop on oil prices. All of these factors have led to a significant decline in extraction costs, relative to just five years ago when the Bakken boom began.

The North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources estimates break-even prices on the best sites in the state to be about $29 a barrel. Figure 3 presents data published in the Wall Street Journal, which presents the range of break-even costs for U.S. shale that includes production areas besides the Bakken. It shows breakeven prices in a range between the inexpensive Saudis and capital intensive projects, like the Canadian Tar Sands.

What does all this mean? Most experts believe that oil prices will once again turn upward as worldwide demand grows and existing reserves of oil diminish. Exploration and drilling will resume first at the most cost effective sites. This suggests that the Bakken is well positioned to benefit early from increased activities, while large capital intensive projects in the Arctic, deep water drilling and the tar sands may be much further down the list.