Like most, if not all Western states, Montana is blessed with a seemingly endless variety of environmental endowments. Many of our natural resources can be used by the economy in one of two ways. First, land can be used as a direct input for the production of other goods, e.g. timber or coal. Secondly, the land can be used as an amenity.

Land amenities are defined as the value derived from the land – uses other than as a direct input to production, such as from recreation or environmental, cultural, historical, wildlife and nature conservation value. Land’s use value is defined in terms of how much people enjoy it as a service, such as for tourism.

Roughly 37.5% of Montana is publicly owned land with a variety of uses, mostly in the western third of the state. The land is managed by numerous state and federal agencies who must balance the resource versus amenity characteristics of the environment. The underlying question is: Do land amenities lead to economic growth and prosperity?

First, we need to define a couple of terms. Economic growth refers to the long-run steady march of economic progress over long periods of time, say 30 years. Progress at the regional level is generally measured using familiar concepts, such as total income and overall employment. However, total income and employment are not generally good measures of economic development. Economists agree that what causes growth are changes in productivity and, on aggregate, population growth. In turn, productivity is the result of the accumulation of skills, ideas, innovation and/or improved institutions. Economic growth is an appealing goal as it leads to improved standards of living, better health, more leisure and improved environmental quality.

On the other hand, short-term economic fluctuations are caused by transitory events, such as business cycles and other shocks to an economy, like a disaster or government stimulus spending. The effects of these shocks are generally short lived – less than say five years – and have no permanent effects, all things being equal. Natural disasters can be very painful in the short run, but they usually die out quickly. The 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California’s Butte County destroyed the town of Paradise. While employment has yet to fully recover, in terms of income it had no lasting impact.

Research to Date

Much of the research on the relationship between land amenities and growth does find a positive and sometimes statistically significant relationship between land amenities and income, migration, employment, real estate prices, etc. However, the results only demonstrate significance over short periods of time and rarely have a positive impact on real earnings, which is the preferred measure economic activity. Therefore, analyses that rely on short time frames exaggerate the effects of land amenities on economic performance and may be confused with economic growth.

This reflects the so-called “paradox of plenty” or the “resource curse,” which refers to the inability of resource- rich economies to fully benefit from their natural resource wealth. This is applied to the use of resources as production inputs and the same logic applies to land amenities as well. In other words, if an economy puts all their eggs in the resource amenity basket without diversifying their economic portfolio, it sets the region up for boom and bust cycles.

Therefore, to understand how amenities impact economic growth, we need to extend the time horizon. Studies conducted by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research and others demonstrate that over longer time frames land amenities have a statistically significant positive effect, but in some cases, they have a negative effect on growth. The reason is relatively straightforward – any positive economy wide shock will increase wages and income because tourism rises. But because the amenities are fixed over time, their additional impact declines in the longer run.

Viewed through this lens, when analysis does find that amenities do increase income and employment, the results should be interpreted as amenities attract income and employment, via migration, not necessarily drive income. As it turns out, over time real per capita earnings, often used as a proxy for economic growth, tend to be negatively related to amenities or not statistically significant. This makes sense – if amenities attract income to small regional economies, holders of wealth tend to buy hospitality and leisure services that generally offer lower wages and may, in fact, crowd out other sectors.

Land Amenities and Economic Growth in Montana

To see the effects of productivity and land amenities on growth, let’s consider two similar counties in Montana – Flathead and Gallatin. Yellowstone County is also included as representative of a more traditional agricultural and industrial economy.

According to a recent report by the Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research at the University of Montana, Flathead and Gallatin counties have the largest share of nonresident spending in the state. Flathead County’s economy has many tourist attractions, such as Glacier National Park, Whitefish Mountain Resort and Flathead Lake. Gallatin County borders Yellowstone National Park and has one of America’s largest ski resorts (Big Sky Resort), as well as other areas of protected land. A key distinction is that Bozeman is home to Montana State University and has become a center for the state’s high-tech industry.

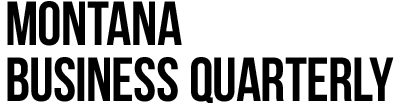

To compare differences across the two counties, Figure 1 shows inflation adjusted, or real per capita earnings, which is defined as income derived solely from labor income for 2001 to 2019. Given that formal county level productivity data is not available, economic theory can demonstrate that real earnings can be used as proxy for productivity, the driver of economic growth. Income comes from a variety of additional sources – interest income, rental income, transfer payments, etc. – and therefore can overstate the level of regional economic activity. For example, a trust funder working at a bar may take home relatively little in terms of earnings, but may also receive substantial income from owning other assets.

As the data in Figure 1 shows, 2001 real per capita earnings in Gallatin County were below both Flathead and Yellowstone counties, but accelerated sharply in 2002. 2012 was notable as the year Bozeman based RightNow Technologies was bought by Oracle. This is generally credited as the beginning of Bozeman’s tech boom, but the data suggest the seeds of tech innovation were sown earlier.

In Gallatin County, real per capita earnings averaged 2.2% growth per year between 2001 and 2019. Over the same period, Flathead and Yellowstone counties real per capita earnings grew 0.8% and 1.6% respectively. This may not seem like a big difference, but at those growth rates Gallatin County’s real per capita earnings will double in roughly 32 years. Meanwhile, in Flathead and Yellowstone counties it will take 88 and 43 years, respectively.

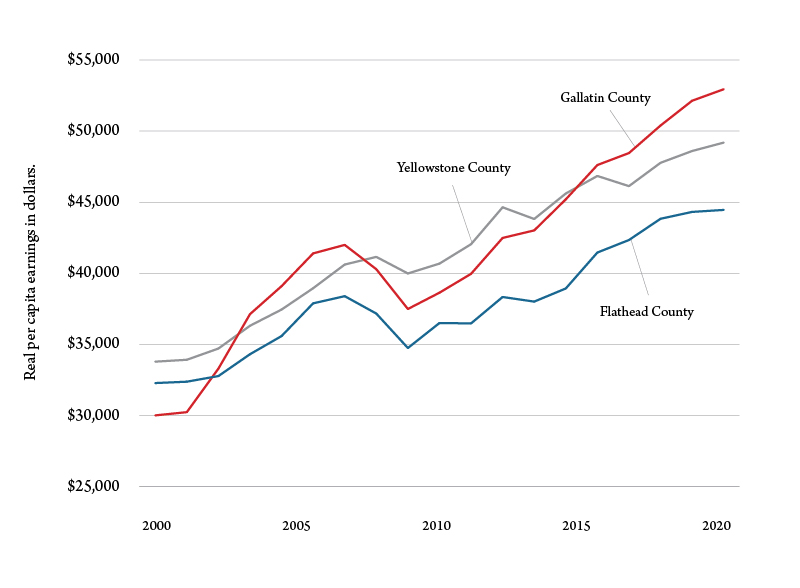

What determines these differences is productivity? As a hub of the tech industry and the ancillary institutions and businesses associated with technology, productivity in Gallatin County is relatively high and contributes to higher long-run growth. Figure 2 shows the change in productivity in Gallatin County minus the change in productivity in Flathead and Yellowstone counties. Productivity growth in Gallatin County is on average 1.5% higher than Flathead County and 0.8% higher than Yellowstone County. But we do see that productivity in Flathead County is rising relative to Gallatin and the opposite for Yellowstone.

This is where communities like Bozeman provide a blueprint for other economies wishing to reduce the risk associated with the resource curse. Bozeman is able to attract highly skilled workers who want to enjoy regional land amenities, which does attract income. Revenues generated in the tourist sector can be used to leverage an innovation sector, one specific to the region to drive productivity and long-lasting economic development.

Clearly, one size does not fit all. Bozeman has the advantage of having a high-quality research university in its city limits, but other regions could adapt some version of this model. Kalispell has a tertiary research and academic medical center and could provide incentives to support the local development of productivity.

This article is not about whether or not resources or amenities should be protected, but rather how small local economies can sustain viability in the face of continuous short-term business cycle fluctuations. The long-term health of Montana’s land amenities relies on the higher incomes associated with growth because as incomes rise, people are willing to buy greater access to environmental amenities, improving the quality of life and vibrant economies.