What would the economy of Ravalli County, Montana, look like today if harvests of timber from its federally owned lands had remained at levels experienced 30 years ago? In one sense, it is a moot question. Timber harvests declined, mills in the region closed and the economy grew in a different direction – changing the past is not a feasible policy option.

Yet history can teach us how past events and policy decisions have affected current economic performance, which can help inform decisions that will affect the future. It is in this spirit that researchers at the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana examined the question of “what if.” They prepared a picture of economic activity in the local economy as it might have looked if past land management decisions would have been different.

The project took into account the profound changes in sawmill and other wood processing technologies that have changed the scale and labor needed at facilities today. It also employed the judgment of BBER forest products researchers to make reasonable projections as to what mill capacity could have been sustained in the county if timber harvest volumes from adjacent federal lands been maintained.

The results of the analysis suggest that in the absence of the timber harvest declines, which began in the early 1990s, the Ravalli County economy would have significantly more jobs, income and population than exist today.

Timber Harvests and the Wood Products Industry in Ravalli County

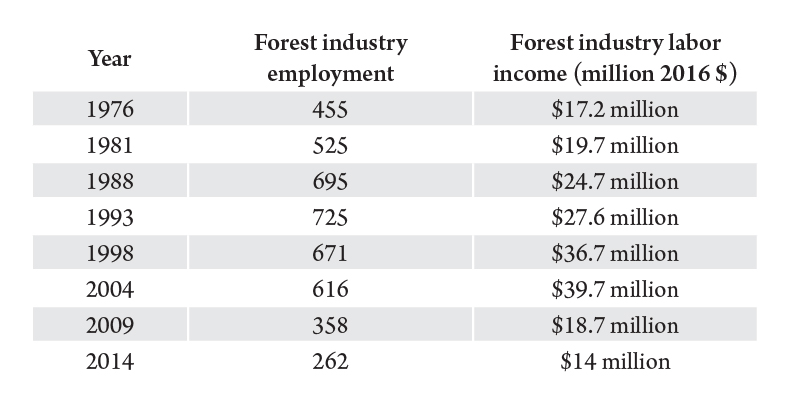

As in many western communities with a timber heritage, the forest industry in southwestern Montana has undergone dramatic changes. Just 17 primary wood products facilities remained operating in Ravalli County in 2014 (Hayes and Morgan 2017), with a majority of that capacity in the log home sector. By contrast, in 1988 the county’s 29 active facilities had a capacity of 91 million board feet (MMBF) – seven times larger than today.

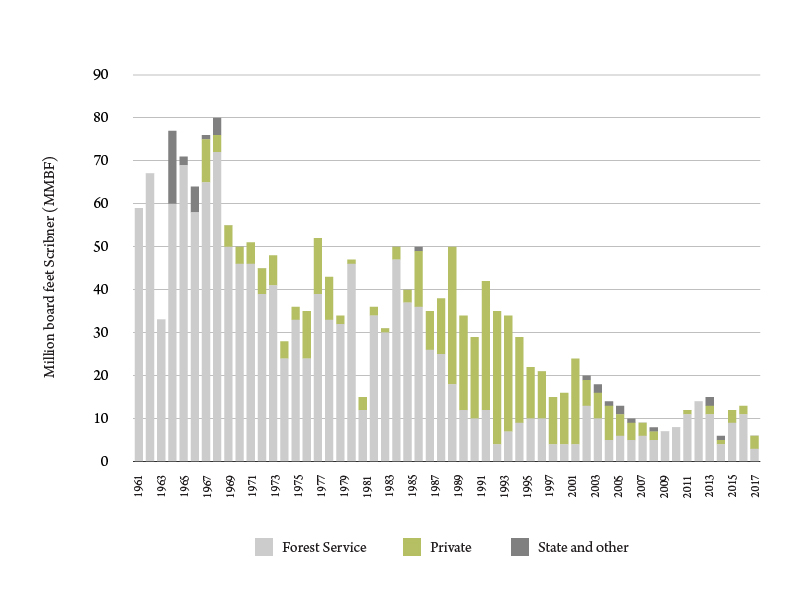

The dramatic decline in timber capacity was driven by declines of similar magnitude in timber harvests (Figure 1). In the late 1980s, the total timber harvest in Ravalli County averaged just over 34 MMBF per year. In the five most recent years with available data (2012-16), average annual harvests were under 10 MMBF.

With approximately 88 percent of the total forestland in Ravalli County under National Forest System (NFS) management, the policies and decisions affecting the Bitterroot National Forest (BNF) timber harvests have been a significant contributor to these industry trends. Between the late 1980s and today, harvests of BNF timber have declined 71 percent. Federal timber harvest reductions and continued low levels of harvests throughout the western U.S. are a direct result of the complex mix of evolving federal land management policies, agency budgets, environmental laws and case law developed from repeated litigation of federal forest management activities – particularly timber related activities (Keele et al. 2006; Miner et al. 2014; Morgan and Baldridge 2015; Keele and Malmsheimer 2018).

Research Approach

This study considered the impact of BNF timber harvest reductions on a) the local forest products industry, and b) the county economy as a whole. We considered what kind of local production capacity could have been sustained if management policies and timber harvest levels for the BNF had remained consistent with harvest levels of the late 1980s. Using an economic model, we estimated the level of economic activity – in terms of jobs, income, production and sales – that could have occurred in the county if policy decisions to reduce those harvests had not been made.

A comparison of this level of economic activity to the one that exists today provided an estimate of the economic impacts of land management policy, which led to reduced timber harvest levels on the BNF.

To better understand the economic impact on Ravalli County of the decline in timber harvests from the BNF, BBER researchers quantified the change in the average annual harvest from the BNF; estimated the direct employment, wages, and product sales value in the forest industry associated with that volume of timber; and used an economic model (REMI) to calculate the broader impact on the county’s overall economy. Rather than speculate what the change would be if timber harvests were to increase, or which mills could have remained in business, this analysis sought to quantify the impact that the decline in harvests had on the county’s economy. While retrospective in nature, this research helps inform decisions regarding future federal land management decisions (e.g., timber harvest levels in BNF plans) that have local economic implications.

This analysis envisioned two economic trajectories for Ravalli County. The baseline (status quo) scenario held current economic activity constant with timber harvests at the 9.8 MMBF level that had been the average for the years 2012-16. The second alternative scenario, considered how the economy could have evolved with annual timber harvests 24.7 MMBF higher, thus holding total harvest volumes at the average level experienced in the 1985-89 period. In the alternative scenario, some of the timber processing capacity lost after that period remained in the county economy, supporting production and jobs. The difference between the alternative and the baseline was the total impact of decreased harvests.

The change in harvests between the late 1980s and the current period (2012-16) represents an average annual harvest volume reduction of 24,378 MBF Scribner. Direct response coefficients (Sorenson et al. 2016) and an assumed product mix of 95 percent sawlogs, 5 percent house logs and other wood products were used to estimate the direct jobs and wages of forest industry workers associated with the harvesting and processing of the timber. The direct response coefficients indicate that eight to 10 jobs in the forest industry are associated with each 1 MMBF Scribner of timber harvested.

The number of jobs varied somewhat depending on what types of facilities received timber and what mix of wood products were manufactured. Product recovery ratios (e.g., how much lumber was produced from each unit of timber) and product prices from BBER mill studies (McIver et al. 2013; Hayes and Morgan 2017b, c) were used to estimate primary product sales values.

The direct forest industry impact of 24.3 MMBF Scribner of timber harvest from the BNF was estimated to be more than 214 jobs, $8.9 million in wages and primary wood product sales of more than $23 million. On an annual basis, an additional 78 forestry and logging jobs, 117 sawmill jobs and 19 jobs in other primary wood products facilities could have been supported by the harvest of 24.3 MMBF Scribner.

Results Summary

The question of how the overall economy would have responded to the jobs, wages and production that might have taken place with higher timber harvest volumes was addressed with BBER’s economic model, leased from Regional Economic Models, Inc. (REMI). The REMI model is a well-known and thoroughly document tool for understanding economic events (Treyz, 1980). Because local wages and purchases supported by wood products create spending and income for local businesses and households, the ultimate effect of higher timber harvests would propagate across the full spectrum of business activity in the county.

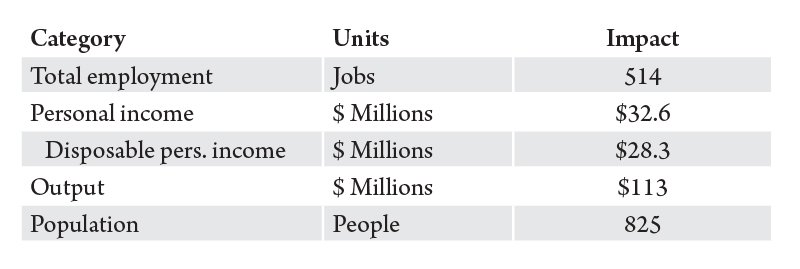

Our basic finding was had timber harvests continued at late 1980s levels, more of the wood products industry in Ravalli County would have survived and as a result, the overall economy would have more jobs, income and population today. A comparison of actual economic activity with what we estimated could have occurred had harvests not decreased revealed that:

- 514 additional permanent, year-round jobs could exist in the county economy today if timber harvests from BNF land had not been reduced.

- Ravalli County households in total could be receiving $32.6 million more in income annually, with $28.3 million of that increase representing disposable, after-tax, income. This includes both forest-related and other jobs in industries such as retail trade (51 jobs), health care (27 jobs) and government (58 jobs).

- Ravalli County businesses could have realized $113 million more in value-added economic production annually.

- The population in the county would likely be higher by 825 people, including 170 school-aged children, if higher levels of timber harvests had been maintained.

All of these impacts represent the difference between two scenarios for the county economy – the actual level of activity and what could have occurred if timber harvests had not decreased. Going forward, we would expect growth in the local economy in both scenarios due to events in other local industries. These impact findings do not change that fact, rather they indicate that the economy with decreased timber harvests is smaller by the magnitudes shown in Table 2.

References

Hayes, S. W.; Morgan, T. A. 2017a. The Forest Products Industry in Montana, Part 1: Timber Harvest, Products and Flow. Forest Industry Brief No. 3. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, Bureau of Business and Economic Research.

Hayes, S. W.; Morgan, T.A. 2017b. The Forest Products Industry in Montana, Part 2: Industry Sectors, Capacity and Outputs. Forest Industry Brief No. 4. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, Bureau of Business and Economic Research.

Keele, D.M.; Malmsheimer, R.W.; Floyd, D.W.; and Perex, J.E. 2006. Forest Service Land Management Litigation 1989-2002. Journal of Forestry 104(4):196-202.

Keele, D.M.; Malmsheimer, R.W. 2018. Time Spent in Federal Court: U.S. Forest Service Land Management Litigation 1989-2008. Forest Science 64 (2):170-190.

Morgan, T.A. and Baldridge J. 2015. Understanding Costs and Other Impacts of Litigation of Forest Service Projects: A Region One Case Study. Missoula, MT: Bureau of Business and Economic Research. 17 p.

McIver, C.P.; Sorenson, C.B.; Keegan, C.E.; Morgan, T.A.; Menlove, J. 2013. Montana’s Forest Products Industry and Timber Harvest, 2009. Resour. Bull. RMRS-RB-16. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 42 p.

Treyz, G. I. 1980. Design of a Multi-Regional Policy Analysis Model. Journal of Regional Science 20: 191-206.