As early as 1791, American women were identified as a potential cheap labor force. That stigma is still playing out today despite the fact that 58 percent of all women participate in the workforce. Women are paid less than men, earning 77 percent of what men earn – the most commonly cited number in discussions about gender wage inequality.

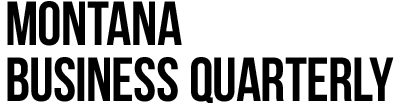

In Montana, women age 16 and older earn 73 percent of what men earn. Indeed, every state in the nation has an earnings gap, but Montana ranks near the bottom at 46th in the nation. (Table 1).

The amount of the earnings gap in the state largely depends on the job sector. Local government workers have the best pay equity with women earning 85 percent of men’s median earnings, followed by federal workers (77 percent) and state workers (79 percent). Private for-profit workers experience the greatest pay inequity – full-time women workers earn only 68 percent of their male counterparts.

The Causes of Gender Pay Inequality

A documented phenomenon called “channeling” (Psychology of Women Quarterly, 2016) shows that from a very early age, social and cultural norms tend to guide women into certain career choices by stereotyping what men and women are best suited to do. Despite significant changes since the 1980s, in the activities and representation of women in society, deeply held beliefs about gender continue.

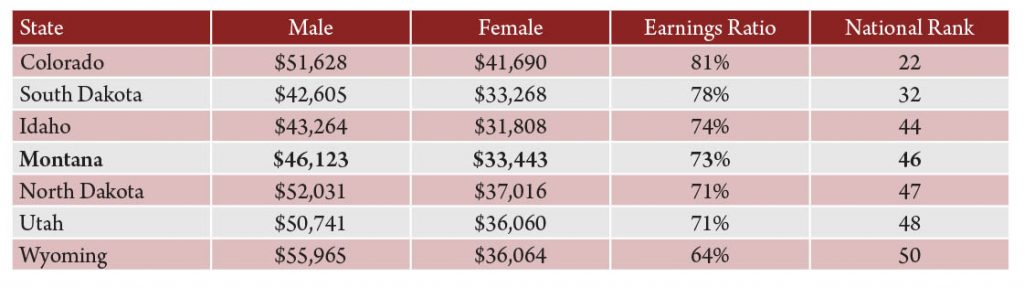

Educational attainment is one of the greatest predictors of future earnings and historically women have had less education than men; but this is changing. In 2012, Montana women out-performed men in attaining associate or bachelor’s degrees. While there was little difference between the numbers of men and women obtaining a graduate or professional degree, their earnings were still lower.

Remarkably, Montana women with less than a high school diploma earn 70 percent of what men earn (compared to 79 percent nationally). Women with graduate or professional degrees earn just 75 percent of what men earn.

Occupations in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) pay more, yet historically few women pursue STEM majors in college. This too is changing. In 2012, 40 to 45 percent of the degrees in math, statistics and the physical sciences were conferred upon women and a majority of biology degrees (58 percent) were earned by women. But when it comes to computer science and engineering majors, women make up only 20 percent of students.

This disparity in educational fields between genders is generally not seen until college, as high school girls and boys earn credits in advanced mathematics and science at similar rates. The good news in Montana is that 32 percent of people working in STEM fields are women, compared with 29 percent nationwide.

Gender segregation by occupation and industry is a major determinant of gender pay inequality. Women in Montana work in the same occupations as they do nationally, but according to 2014 data no industry paid women more than men. The pay gap was closest in the agriculture industry where women earned almost the same as men, although this industry is traditionally male-dominated with only 19 percent of the workers being female. The biggest wage gap was in the finance and insurance industries where women earned 56 percent of what men earn. Women dominate the health care industry, which employs about three-quarters of Montana’s workforce, yet women working in this industry earn 65 percent of what men earn.

Another cause of gender pay inequality is more women work part-time (37 percent) than men (30 percent), thus earning less and gaining less experience to further their careers. More men in Montana work full-time than women and this is not always by choice. Nationally, nearly 5 percent of all women are involuntary part-time workers for reasons such as their hours being cut back or their inability to find full-time jobs. These are women who would work full-time if the hours were available.

The choice to work part- or full-time is rooted in the sexual division of labor in the household and work/family balance. Time out of the workforce due to childbirth is a major factor in women losing ground. Additionally, women tend to take on more child-rearing and household responsibilities than men and are more likely to make work choices to accommodate their family responsibilities. This inequitable sharing of family tasks and responsibilities is less noticeable among families where both partners earn the same amount or when partners hold shift-work jobs with flextime schedules.

In higher-paying careers, men tend to reduce the number of hours they help in the household. By the time a child is 15 years old, the earnings gap between men and women in a two-income family has increased 32 percent. This motherhood penalty results in lowered performance expectations, a lower likelihood of hiring and lower wage offerings. Yet the opposite is true for men, who tend to see wages increase after a child is born and have a greater likelihood of career advancement, known as the fatherhood benefit.

Workplace gender bias in higher level jobs puts constraints on upward mobility, too. There are a disproportionate number of men in leadership positions in Fortune 500 companies. Four point six percent of CEOs, 20 percent of board seats, 25 percent of executive and senior level management positions and 36 percent mid-level management positions are held by women, yet women make up 44 percent of all employees in those same companies. Notably, upward mobility does little to improve gender wage inequality – in fact it does the opposite. Women in higher income percentiles earn less than men, where in lower paying occupations the gap narrows substantially.

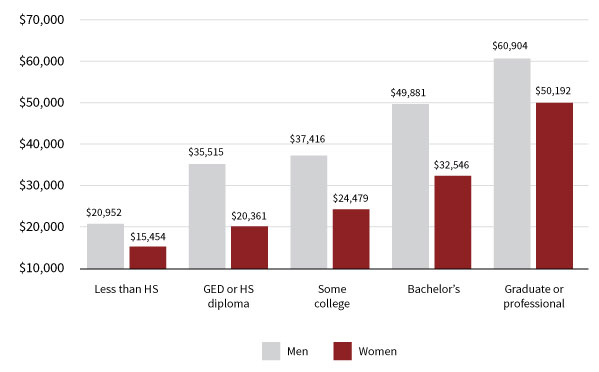

All of these factors play into the wage gap for women of color. While nationally no racial grouping of women earn more than white men, additionally women earn less than men in their own racial group. For instance, American Indian women in Montana earn nearly 93 percent of what all women earn, but only 67 percent of what Montana men earn. Where the difference is most marked is in the total earnings, which takes into account other factors, such as unemployment and underemployment. American Indian women earn 44 percent and American Indian men earn 56 percent of the total Montana male earnings.

Eighty-four percent of American Indian women in Montana have a high school diploma, but less than 10 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher, even though over half of all Montana women have earned some college or above. Overall, the economic and social disadvantages experienced by Montana’s American Indian women add up to less earning power, less education, more rural isolation and more racial and gender discrimination. On a brighter note there are higher rates of Native American women in professional and managerial occupations in Montana than there are nationally.

Montana’s Low-Income Families

Low-income families in Montana are more adversely affected by gender pay inequality than higher earning families – when you start out with less, you end up with less. If gender wage equality were reached for women in poverty it would reduce the number of poor single mothers by nearly 40 percent. If all working women with incomes below the federal poverty line received the same wages as working men, the poverty rate would drop by 43 percent.

Poverty levels in Montana would drop significantly, as 34 percent of female-headed households (with or without children) are at the federal poverty level. This percentage increases for women who head households with children under 18 years old (45 percent) and children under 5 years old (65 percent).

Many women who work to support their families still need to turn to government assistance programs to make ends meet. Nationally, over half of families with children work while receiving food stamps. While bringing women’s wages on par with men’s will not solve the poverty problem, it would reduce the number of families that have to turn to programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid. Reducing the need for government assistance programs is different than reducing the availability of such programs for women and their children. Supporting and strengthening the social safety net should be maintained for those not working or for those earning below the means tests.

Addressing Gender Wage Inequality

Employers can help by taking steps to ensure that workplace policies, such as recruitment, hiring, family leave and internal pay audits, are encouraging to qualified female applicants. Likewise, internal reviews of workplace practices would ensure employers stay welcoming to female employees.

Unstable shift-work schedules, just-in-time scheduling practices and assigning irregular shift times further destabilize workers who are seeking to balance work and families. In addition, without knowing how many hours they will work, a worker’s earnings become uncertain. Over one-third of women hourly workers in their prime childrearing years receive their work schedules with less than one week advanced notice. These unpredictable scheduling practices particularly hit lower income, predominantly female, service workers.

Another area to consider is family leave. Although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 guarantees 12 weeks of job-protected family leave, this only applies to large scale employers and workers with a minimum job tenure, thus half of all workers do not qualify. Remarkably, Montana does not require employers to offer paid medical, family or sick leave.

One last look at Montana is potentially good news for women. According to the Montana 2016 Labor Day Report, the state is facing a labor shortage. Montana’s economy has shown strong growth over the past five years, reducing unemployment and increasing wages. The economy is projected to expand, adding about 9,200 jobs in 2017. However, population data shows that Montana’s labor force isn’t keeping up with demand, adding only 4,500 workers to fill these jobs. So long as women have access to the skills and training demanded by employers they will be able to benefit from the tight labor market, earning wages and benefits equal to their male counterparts.