For many, the first image of Montana is a vast mountainous landscape with pristine forests and rivers, replete with charismatic wildlife. This is the image many business owners hope will attract visitors from around the world. However, there is more to the landscapes of Montana that often go unnoticed. But not for much longer if some advocates of the prairie have a say.

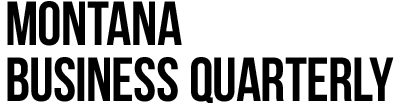

In 2016, nonresident visitors to Montana spent nearly $3.5 billion dollars in the state, directly supporting $4.8 billion in economic activity and more than 52,000 jobs. Visitors flock to Montana for a multitude of reasons – high among them is outdoor recreation. When asked why they come to Montana, an overwhelming number of visitors indicate their desire to visit Yellowstone or Glacier National Park. Given such a response, it is easy to assume that a majority of visitor expenditures, and thus contribution to economic vitality, occur in the regions of the state in closest proximity to the two parks. In fact, year in and year out this is exactly what is observed (Figure 1), with Glacier and Yellowstone Country travel regions accounting for 60 percent of the economic output and 65 percent of the jobs generated by nonresident visitor spending statewide.

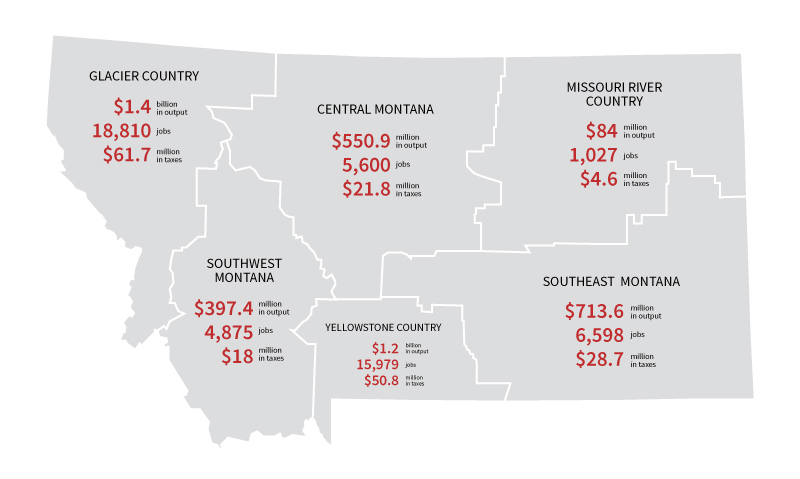

Natural amenity rich destinations like Yellowstone and Glacier are not just a draw for tourists and outdoor enthusiasts on vacation. In fact, much of the population growth of the rural western U.S. since at least the 1990s can be viewed in connection with the proximity to such amenity-rich landscapes. This population growth runs counter to that experienced in many rural, mostly agricultural regions throughout the nation, including much of northeast Montana. Population trajectories since 1970 in Missouri River Country compared with Yellowstone and Glacier Countries are emblematic of these observations (Figure 2). Counties like those in Missouri River Country find themselves in the midst of not only a decadeslong decline in population, but also struggling employment opportunities that keep younger generations in the community. As each community evaluates its path forward, they seek opportunities to engage in an evolving marketplace. Often that marketplace has been found in identifying and taking full advantage of amenity-based recreation and an amenity-based economy.

As Yellowstone and Glacier national parks experience continued record breaking numbers of visitors from across the country and internationally, regions like the Missouri River Country go largely unknown and underexplored. For many locals this may be just as well, as it allows them to go on without the hassle of tourists and other visitors. However, for others, the region is an opportunity waiting.

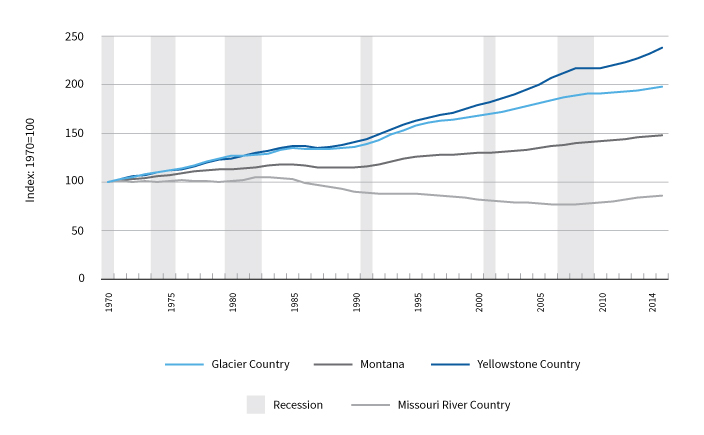

A large expanse of public and private land nestled between Montana’s Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Fort Peck Reservoir to the south, and the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and Upper Missouri River Banks National Monument to the west is currently the focus of one of North America’s most ambitious large-landscape conservation initiatives (Figure 3).

The nonprofit American Prairie Reserve (APR) has steadily sought to establish a multimillion-acre grassland reserve as an intact prairie ecosystem and home for abundant native wildlife. Their aim, and that of proponents of the endeavor, is to provide an array of public recreation, research, tourism and other positive economic impact generating opportunities. To date, the American Prairie Reserve encompasses more than 86,500 acres of purchased private lands and 266,000 acres of leased federal and state public lands. A key element in fulfilling this vision is restoring a herd of several thousand head of bison to the landscape. The reserve first introduced bison to the range in 2005. Since that time, the herd has grown to more than 600 animals.

Proponents of the reserve restoration initiative expect significant increases in outdoor recreation and tourism-based expenditures in the region, making it the third corner of a tourism triangle in Montana, with Yellowstone and Glacier at the other two corners. These expectations are based on the perceived attractiveness of the prairie and bison as a natural amenity. Such visitor expenditure increases, if brought to fruition, may serve to support the struggling economy of northeastern Montana. However, the expected magnitude of future new spending is uncertain. Additional uncertainty may be found in any negative economic impacts generated if active range lands, a primary economic driver of the region, are removed from production or reduced in their productivity.

The economic and social uncertainties of northeast Montana and an interest the role tourism may play in its future, generated the push for a study by the Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research (ITRR) at the University of Montana. The study, funded by a grant from the National Wildlife Federation and ITRR funds directed from Montana’s Lodging Facility Use Tax, created a first look at the social and economic impacts of the natural amenity enhancement.

Whether it is Montanans traveling for a weekend away or out-of-state visitors spending a longer vacation in the region, the opportunity to attract visitors – and thus spend money – is largely dependent upon the perceptions these potential visitors have of the region, and their willingness to go explore it.

In a survey of more than 600 nonresidents, researchers at ITRR found that many nonresidents who have not been to northeast Montana do not know much about the region. In fact, roughly three-quarters of these respondents indicated that they did not know enough about the region to form an opinion about some of its most emblematic attributes – the cultural history, wildlife viewing, hunting and fishing, native culture, dinosaur sites, and unique geologic and water features. The lack of a quality image of the region readily speaks to the low visitor spending numbers. Much of the region is far from anything else. Without a major known draw, a lot of visitors to Montana simply do not make it to the northeast stretches.

Adding to the concern of this lack of knowledge are the number of visitors who have a lower perception of the area than those who have not been there at all. Visitors to the area reported a significantly lower perception of quality and intrigue in the region’s native culture and wildlife viewing opportunities.

This is perhaps where the efforts by the APR may drum up interest in visitors to the region and enhance their experience once there. A quarter of nonresidents surveyed by ITRR indicated plans to travel to the region in the next year and spend an average of 2.6 nights. However, only 13 percent of them had ever heard of the American Prairie Reserve – and these are largely people who have been to Montana before or previously expressed interest in coming. Montanans outside of the northeast region also had a rather low familiarity with the APR, with only 32 percent knowing about the effort.

Once respondents were provided with more information about the current efforts of the APR and the conditions on the ground, those who had already planned to travel to and stay in the region expressed a greater interest in staying longer in the area – 26 percent more expressed a desire to visit. Additionally, once the respondents were provided with a broader look at the ultimate goals of the APR, visitation interest jumped even more.

The broader vision of the APR includes 3.5 million acres of connected public and private lands – roughly the size of Connecticut – with enhanced bird and riparian habitats, reintroduction or expansion of native wildlife species like the swift fox, prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets, 10,000 bison, hut-to-hut overland trekking and paddling opportunities on the Missouri River.

The economic impact resulting from the stated increased interest in visiting the American Prairie Reserve and northeast Montana is significant. In 2015, nonresident visitors spent $113 million in the region. Under conditions of a full build-out, this spending could be increased by as much as 67 percent, yielding $56 million in additional economic output and nearly 700 additional jobs.

While the vision of the American Prairie Reserve is still years in the making, the opportunity to increase awareness of the natural amenities that currently exist in northeast Montana is happening now. Obviously, if the goals of the APR come to fruition and visitor response follows, improvements in infrastructure are greatly needed. A desire for improved and expanded dining and lodging opportunities, and roadways were frequently cited by respondents to ITRR’s survey.

Time will tell if northeast Montana is able to transform itself into that third corner of an outdoor recreation triangle in Montana. It certainly has several dedicated tourism and conservation groups that believe it has the merits to stack up. Success may come down to the capacity of the region to maintain its cultural heritage and engage in an amenity economy.

Agriculture has been and will continue to be a major contributor to the way of life in the region. As such, the potential negative effects generated by any removal of lands from productive use must be considered in concert with the gains to recreation and tourism. The two objectives – agricultural production and recreation and habitat enhancement – are not necessarily at odds. Proponents of the APR have sought market-based mechanisms to align their objectives with that of the agricultural communities. Such market-based activities include the continuation of grazing opportunities where potential conflict is limited, as well as the promotion of products produced by local ranchers working in concert with conservation efforts. The goal of such activities is the ability to increase the overall welfare for the communities, not just those directly benefiting from conservation efforts and increased recreation.