Housing has always been a public policy priority. Governments that cannot put roofs over the heads of their citizens are not judged kindly by either their people or by history. In the United States there are dozens of policies aimed at making it easier for Americans to own or rent housing. These range from national policies, such as the tax deduction of mortgage interest to the provision of subsidized housing in local communities. The fact that housing prices continue to rise faster than income and that a high fraction of families are stressed by housing costs – or they have no housing at all – tells us that much work still needs to be done.

One category of housing policies that are targeted explicitly at low-income households are known as affordable housing programs, and the housing units they subsidize are known as affordable housing. Collectively these programs form a key part of the safety net that provides part of the daily necessities of life to families, individuals and their children who are most in need. In Montana, those programs are oversubscribed and face daunting challenges.

The Bureau of Business and Economic Research recently delivered a comprehensive report of those challenges (Bridge, 2020). This article highlights the findings of that report.

Affordable Housing Programs in Montana

There are currently over 23,000 housing units in Montana that are supported by one or more affordable housing programs. This is a substantial number, yet in comparison to the more than 510,000 housing units of all kinds in the state, it is clearly a tiny segment of the market. That number is also low relative to potential demand, amounting to 39% of the number of households who earn extremely low incomes, defined as 30% or less of local median income.

Most support for housing subsidies comes from federal government programs, often with state match and state participation. The success or failure of these programs can hinge on how successfully states pursue this federal support.

The most important of these programs in Montana include:

- The federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program awards nonrefundable tax credits to developers (who then sell them to investors) to raise cash for construction of units with restricted rents. There are currently 7,977 apartments for rent in Montana that were developed using the LIHTC program as the majority funding source, including new and rehabilitated units.

- There are 11 local housing authorities in Montana that own and manage 2,009 public housing units, whose tenants pay an average of $321 per month in rent and whose average annual household income is $13,658.

- The Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act offered block grants, infrastructure resources and assistance in obtaining support for other programs to the more than 500 federally recognized tribes. There are 5,972 public housing units managed by seven Montana tribes.

- The Home Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) initiated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 1990 provides block grants to governments, affordable housing authorities and nonprofits to build, acquire and/or rehabilitate both apartments and single-family homes. In return, those units are made available to low-income households at subsidized rates. The HOME program includes down payment assistance. There are 1,076 housing units in Montana currently being subsidized by the HOME program.

- Community Development Block Grants are available to general-purpose local governments, such as counties, cities and towns to help fund single and multi-family construction and rehabilitation projects.

- Individual and Project-Based Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers provide rent subsidies to very low-income households, elderly persons and persons with disabilities. The two types of vouchers differ in that project-based vouchers are attached to buildings, rather than individual renters. There are currently 4,319 housing units in Montana being subsidized by Section 8 programs, of which 1,500 are targeted for families earning low incomes.

- The USDA Rural Development programs offer loans, guarantees and other credit support for housing development in rural areas for low-income households. One of those, the Section 515 program has ultimately subsidized 1,737 housing units across the state, with a very large proportion of those in less populous counties.

- The Multifamily Coal Trust Homes program was created by the Montana Legislature in 2019 to develop or preserve rental apartments that are affordable to working families, seniors and persons with a disability. The loans awarded have financed seven developments with a total of 252 units.

Key Challenges for Montana’s Housing Programs

“Poverty programs will always be poor programs,” said former U.S. Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Wilbur Cohen in the 1960s, and there is no question that the programs directed at helping low income Montanans secure adequate housing are starved for resources.

Since 2016, there have been over 30,000 applications for housing choice voucher programs, yet in that same time frame only about 4,000 have been issued. Other programs display sizable gaps between demand and availability.

Homelessness

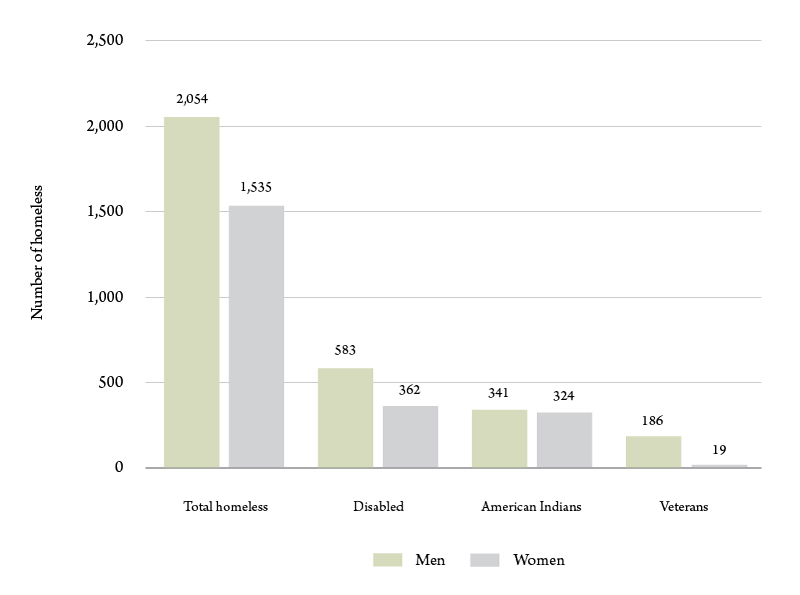

The rise in the number and visibility of homeless individuals and families in Montana is perhaps the best reminder of this shortfall. The Montana Homeless Management Information System estimated that in 2020 there were more than 3,500 homeless statewide in that year. As shown in Figure 1, the disabled and American Indians comprise a significant fraction of the overall homeless population.

The costs borne by homeless individuals and families are stark and clearly visible. The instability caused by homelessness makes finding many basic necessities nearly impossible – adequate food, shelter, clothing, washing facilities, transportation, health care, education, personal safety and security, and employment. These challenges are compounded by the high levels of substance abuse and mental illness experienced by homeless individuals and families.

Loss of Affordable Housing Units

Low-income Housing Tax Credit program properties must commit to a 30-year period of affordability, but they are only subject to a 15-year compliance period. This is the period of time where the tax credits that have been given to developers can be taken back or recaptured if the property fails to comply with LIHTC regulations, which is a rare occurrence. During the following 15 years (or more), the property is still required to maintain affordability and comply with LIHTC rules and regulations. Though without the ability to take back the credits, the states do not have many enforcement options for compliance.

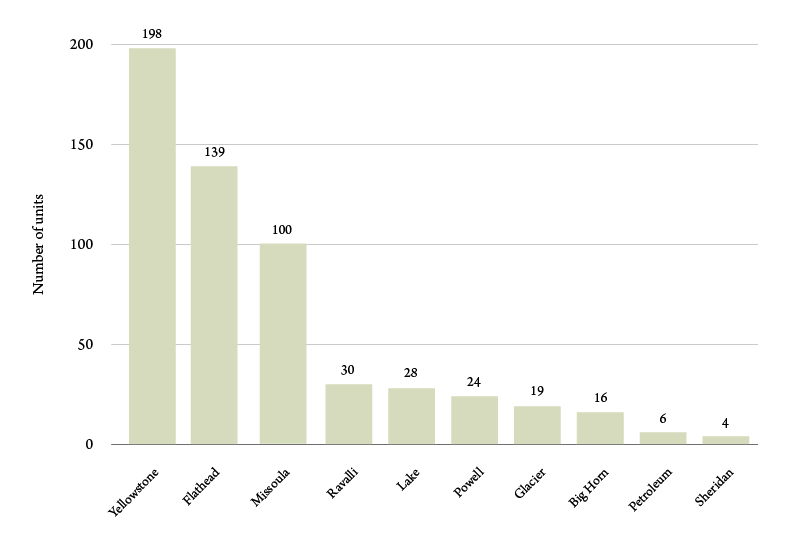

In areas with relatively booming housing markets, selling the property may be a more attractive option than continued compliance. Over the next five years, 564 LIHTC housing units in Montana will be facing the potential of being lost to the market. Figure 2 shows the number of these housing units by county. Notably, the majority of units with the potential of being lost to the market within the next five years (77%) are located in counties with relatively high affordability challenges.

Underutilization of Federal Resources

Since 2012, Montana has only financed 717 affordable housing units (including acquisition, rehabilitation and new construction) with federal 4% low-income housing tax credits. This illustrates the difficulty this program has for attracting developers in Montana. In this same period of time, Montana has abandoned $949 million in tax-exempt private activity bonds. Private activity bonds are revenue-backed bonds issued by a state or local authority for a private project. These bonds are exempt from federal income taxes, which enables the project to access capital at a lower interest rate than could otherwise be attained. When they are unclaimed for a period of years, they are abandoned.

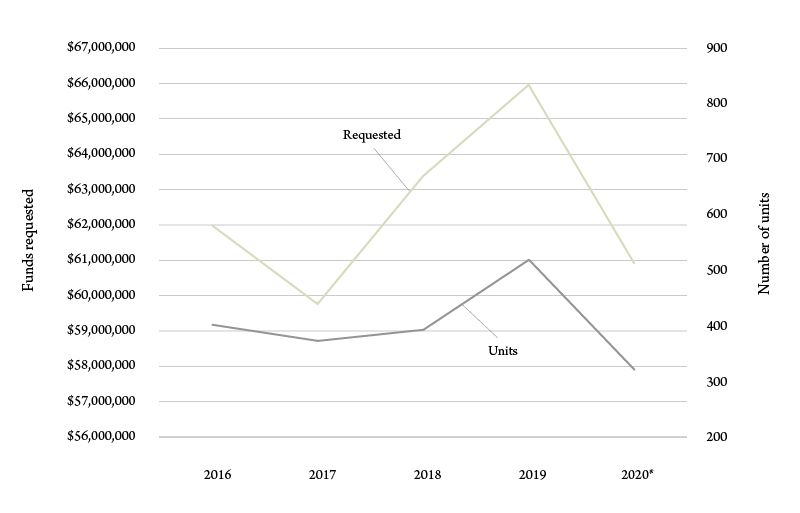

Since 2016, an average of $62 million per year in 9% low-income housing tax credit requests have been denied due to a lack of funding (Figure 3). These projects would have significantly expanded the inventory of affordable housing in Montana. A state LIHTC program similar to those implemented in other states would likely allow developers to leverage the 4% federal tax credits, which are currently unutilized in order to increase the supply of affordable housing in the state.

Conclusion

The United States as a whole is currently facing a shortage of affordable homes and Montana is no exception. With relatively few affordable homes available for households earning a low income, and with much of the existing affordable inventory aging and in need of rehabilitation, many households earning a low income are being priced out of housing markets. We are now facing ever expanding economic challenges, and these issues and concerns are not going away or getting better. When housing becomes unaffordable, it imposes costs on entire communities, but the most vulnerable in society bear the brunt of those costs. Housing affordability will likely be a challenge that Montanans continue to face in the coming years, and as such it deserves a place in public conversation.